Atatürk's Populism Principle and Working Life

Character Size

"The principle of populism is undoubtedly one of the fundamental elements of our Republic and is the most important factor that will help us understand certain developments in Atatürk's era, which are still the subject of debate."

Atatürk's Populism Principle and Working Life

The principle of populism is undoubtedly one of the basic elements of our Republic and is the most important factor that will help us understand certain developments in Atatürk's period, which are still the subject of discussion. Today, it is clearly known that Atatürk and his close circle looked at many problems, from multi-party democracy to economic development, from the problem of political regime to working life, within the framework of this populist philosophy. However, first of all, it is necessary to reveal what we should understand from populism and how such a thought pattern is reflected in concrete policies. In order to do this, first of all, it is necessary to examine the historical origins and evolution of the understanding of populism and then how it came to Turkey and integrated with the leading staff of the Republic.

The process, which started with the Cromwell Revolution in England in 1640, carried out a major political transformation with the change of parliamentary structure in 1688 and ended with the Industrial Revolution that started in the same country and the French Revolution in 1789, about a hundred years later. One of the most important features of this process is that it shows that Europe has completely left the medieval order behind in terms of politics, economy and culture. The concept of sovereignty based on religious authority, which reached its zenith in the Middle Ages with Thomas Aquinas, in other words, the theological worldview gave its place to the concept of popular sovereignty, the theocratic state understanding was completely denied with the reform movement within Christianity itself, and the secular state concept has developed. 1 The king or monarch, who received all his ideological power from religious authority and the church, which is its representative on earth, was replaced by a monarchy limited to only symbolic powers in England and a republican regime in France with the complete abolition of the royal regime. The development of a private entrepreneurial new economic order, which reinforces this great transformation and is another part of the same process, emerged as the victory of reason and science with the Industrial Revolution. The concept of belief in the Middle Ages left its place to rational thought, and the aristocratic view, which separated people from birth and placed them in certain categories, was destroyed after long struggles, and concepts such as equality of opportunity and equality before the law were developed. It not only symbolized a technological development, but also led to the creation of a new human type, the rooting of new understandings and the formation of new philosophical systems. Now, this new man rejects the oppressive, interventionist and inclusive, absolute state authority of the Middle Ages, and does not see even the slightest intervention in the automatic functioning of market mechanisms in economic life. This person wants equal conditions of competition, confronts differences in social status, and demands only the protection of life and property from the state. It basically looks at the problem of religion as a matter of conscience, and advocates the principle of popular sovereignty based on universal suffrage and broad political participation, instead of the centuries-old domination of the church since the collapse of Rome. It has led to the rooting of new understandings and the formation of new philosophical systems. Now, this new man rejects the oppressive, interventionist and inclusive, absolute state authority of the Middle Ages, and does not see even the slightest intervention in the automatic functioning of market mechanisms in economic life. This person wants equal conditions of competition, confronts differences in social status, and demands only the protection of life and property from the state. It basically looks at the problem of religion as a matter of conscience, and advocates the principle of popular sovereignty based on universal suffrage and broad political participation, instead of the centuries-old domination of the church since the collapse of Rome. It has led to the rooting of new understandings and the formation of new philosophical systems. Now, this new man rejects the oppressive, interventionist and inclusive, absolute state authority of the Middle Ages, and does not see even the slightest intervention in the automatic functioning of market mechanisms in economic life. This person wants equal conditions of competition, confronts differences in social status, and demands only the protection of life and property from the state. It basically looks at the problem of religion as a matter of conscience, and advocates the principle of popular sovereignty based on universal suffrage and broad political participation, instead of the centuries-old domination of the church since the collapse of Rome. it rejects the absolute state authority and does not justify even the slightest intervention in the automatic functioning of market mechanisms in economic life. This person wants equal conditions of competition, confronts differences in social status, and demands only the protection of life and property from the state. It basically looks at the problem of religion as a matter of conscience, and advocates the principle of popular sovereignty based on universal suffrage and broad political participation, instead of the centuries-old domination of the church since the collapse of Rome. it rejects the absolute state authority and does not justify even the slightest intervention in the automatic functioning of market mechanisms in economic life. This person wants equal conditions of competition, confronts differences in social status, and demands only the protection of life and property from the state. It basically looks at the problem of religion as a matter of conscience, and advocates the principle of popular sovereignty based on universal suffrage and broad political participation, instead of the centuries-old domination of the church since the collapse of Rome. it confronts social status differences and asks the state to protect only life and property safety. It basically looks at the problem of religion as a matter of conscience, and advocates the principle of popular sovereignty based on universal suffrage and broad political participation, instead of the centuries-old domination of the church since the collapse of Rome. it confronts social status differences and asks the state to protect only life and property safety. It basically looks at the problem of religion as a matter of conscience, and advocates the principle of popular sovereignty based on universal suffrage and broad political participation, instead of the centuries-old domination of the church since the collapse of Rome.

The material developments that we tried to describe above and the creation of a new human type, which is the product of them, were reflected in the intellectual life as well, and the theological view was largely abandoned. Numerous works were published in the period from the seventeenth to the beginning of the twentieth century. However, these social and political currents of thought did not follow a single line, and even though they were in the same worldview, they showed great differences among themselves. The dominant view, especially in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, contrasted the socialism of the Middle Ages with the view emphasizing the superiority of the individual and its protection against the state and society. The idea of “Society is nothing but the sum of individuals” has come to the fore and the organic unity of society, its internal relations and social groupings and stratifications in the rapidly changing world have been ignored. It is possible to find the best example of this in social contract theories.4 These theories, especially put forward by Rousseau and Locke, briefly claim that society is a historical formation that individuals create with their free will and guarantee with a contract. In other words, before the emergence of societies, it is assumed that there was a period in history where people or families lived one by one, and then it is said that these individuals entered social life in return for a contract in order to ensure the safety of property and life. The point is that the rights of the individual are protected by the state, or rather, is the need to protect the individual against the state and society. Otherwise, according to the provisions of the contract, the individual may have a choice to leave the society and live independently again. In fact, there have been some thinkers who claim that it can even lead to the right of resistance as an individual's natural right. 5

As can be seen, the individualism movement, which sacrifices social or group interests to individual interests, was the focus of liberal thought at first. However, the new social structure brought about by the Industrial Revolution in particular has led to changes in these ideas over time and has revealed that the problem in social life is not that simple. current was born. 6

Hume, Godwin, Bentharm and Mill in England; In France, the utilitarianism led by Helvetius, although not a uniform thought, acted jointly in order to combine the benefit of the individual and society. Again, the starting point is the individual. In other words, the requirements of the happiness of the individual in social life are investigated. Here, too, society, as in classical liberal thought, consists of the sum of individual individuals, and what will be beneficial to the public is that the greatest number of individuals is the happiest. For this, people should not only think about their own interests, but also act in line with the interests and well-being of their neighbors and finally the whole society. What actions, using what moral standards, can best benefit neighbors and society? In other words, Which of our actions do the least harm to people other than ourselves? At this point, goodwill and the ability to think multilaterally seem to be the two basic elements recommended in terms of providing public interest. 7 Only in this way will the individual's conscience be satisfied and thus have more happiness. As can be seen, the starting and ending points of this philosophical system are individuals; society or the public interest, in the end, only serves as a catalyst for the glorification of the individual. However, utilitarianism went one step further with the introduction of concepts such as public interest and society compared to the dominant individualist view in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. appear to be two basic elements recommended in terms of providing public interest. 7 Only in this way will the individual's conscience be satisfied and thus have more happiness. As can be seen, the starting and ending points of this philosophical system are individuals; society or the public interest, in the end, only serves as a catalyst for the glorification of the individual. However, utilitarianism went one step further with the introduction of concepts such as public interest and society compared to the dominant individualist view in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. appear to be two basic elements recommended in terms of providing public interest. 7 Only in this way will the individual's conscience be satisfied and thus have more happiness. As can be seen, the starting and ending points of this philosophical system are individuals; society or the public interest, in the end, only serves as a catalyst for the glorification of the individual. However, utilitarianism went one step further with the introduction of concepts such as public interest and society compared to the dominant individualist view in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. it only acts as a catalyst for the glorification of the individual. However, utilitarianism went one step further with the introduction of concepts such as public interest and society compared to the dominant individualist view in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. it only acts as a catalyst for the glorification of the individual. However, utilitarianism went one step further with the introduction of concepts such as public interest and society compared to the dominant individualist view in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

The positivism movement, which, although also included in the liberal thought system, gave weight to the social view and formed the last link of this system with its development in the nineteenth century, brought a new understanding of society with its line extending from Comte to Durkheim.8 Especially Durkheim's social organism and social structure. Although the concepts of division of labor did not foresee a major transformation in the society in which he lived, he shifted the focus of political thought from the individual to the society. Here, society is almost likened to a living organism, made up of cells that act as a whole and complement each other, rather than as a collection of individual elements. Therefore, we can distinguish the parts of this whole from each other only through the division of labor or in terms of their different functions. In other words, society is not the conflict area of individuals and groups, but

Turkish society, which has not passed through these economic and political phases experienced by Western societies, has passed on to this last mentioned solidarist view, not individualist thought patterns. In the Ottoman Empire, naturally, the dominant ideologies emerged as religion and Ottomanism. In the development of pre-republic secular thought, this monotheistic view, which was suitable for the structure of our society, also rejected religious ideology and influenced a section of Turkish intellectuals to a great extent. Ziya Gökalp acted as the most important bridge in the entry and spread of this view in Turkey. Ziya Gökalp explains his understanding of populism with these words: 9 “The presence of certain strata or classes within a society shows that there is no internal equality. Therefore, the aim of populism is to remove the strata and class differences, It is to confine the different groups of the society to the occupational groups that were born only by the division of labor. In other words, populism concludes its philosophy with this motto: There is no class, there is a profession!”

As can be seen, Ziya Gökalp has been the representative of the monotheistic view in Turkey by adhering to Durkheim's concept of social division of labor.10

Later, within the Kadro operation, the view of the society was expressed as follows: “In our opinion, the Turkish nation is as whole inward as it is outward. We consider class and group quarrels, class and group domination within the nation, as external movements that shatter the unity of the nation, whether from below or from above. The elimination of class domination is one of the advanced principles of national liberation movements. First and last is the national interest. Therefore, the Kadro is a social holistic in the way of considering the community.”11

Atatürk, who closely examined the currents of political thought in the Western world, as well as the phases these societies went through and especially the French Revolution and the ideas it brought, was naturally kneaded in these influences and formed his own views in this environment. In other words, he established organic ties with the positivist thought in the West12 and while doing this, he did not ignore the historical characteristics of Turkish society and the conditions of that day for a moment. Therefore, Atatürk was not oriented towards a Turkish-Islamic synthesis, on the contrary, towards a Turkish-secular Western synthesis. He clearly expressed this in his speech in Balıkesir in 1923: “This nation has been hurt more than political parties. Let me tell you that sects in other countries have been established and are still operating for economic purposes. Because there are different classes in those countries. A political party is formed to protect the interests of one class, and another party is formed to protect the interests of the other class. This is very natural. The results we have witnessed because of the sects that seem to have formed as if there were separate classes in our country are well known. However, when we say the People's Party, it does not include a part, but the whole nation. Let's review our people again: You know that our country is a farmer's country, so the majority of our nation's determination is also farmers. When this happens, large landowners come to mind against it. How many people own large land in our country? What is the amount of this land? If it is examined, it can be seen that no one owns a large land compared to the size of our country.

Then came the small merchants who traded in the towns with the art owners. Of course, we have to ensure and preserve their interests, conditions and attitudes. Just like the big land owners we assume are against the farmers, there are no people with big capital against these traders.

Then it comes to work. Today, establishments such as factories, factories, etc. are very limited in our country. The amount of our current labor does not exceed twenty thousand. However, we need many factories to raise the country; work is required for this. Therefore, it is necessary to protect and protect the workers who are no different from the farmers working in the fields.

After that, intellectuals and zevat called ulama come. Can these intellectuals and ulama gather on their own and become enemies of the people? The duty entrusted to them is to enter the people, to guide them, to raise them and to guide them to progress and reflection.

This is how I see our nation. Consequently, since the interests of the connoisseurs of various professions are in harmony with each other, it is not possible to divide them into classes, and they are all made up of the people with their general committee.”

Although Atatürk's view of society is a monolithic view, it also includes other features. In his eyes, according to the principle of populism, the source of power is directly in the people themselves, which manifests itself clearly in the organization of the War of Independence and the participation of all segments of the society in the national front. Atatürk's understanding of populism really aimed at the freedom and equality of the nation, which in fact indicated his trust and belief in a democratic system. In other words, according to him, a social structure consisting of groups that complement each other with their different functions was not sufficient. Such a structure should have been supported by a liberal and egalitarian political regime dominated by the people. The Freestyle trial proves this notion.

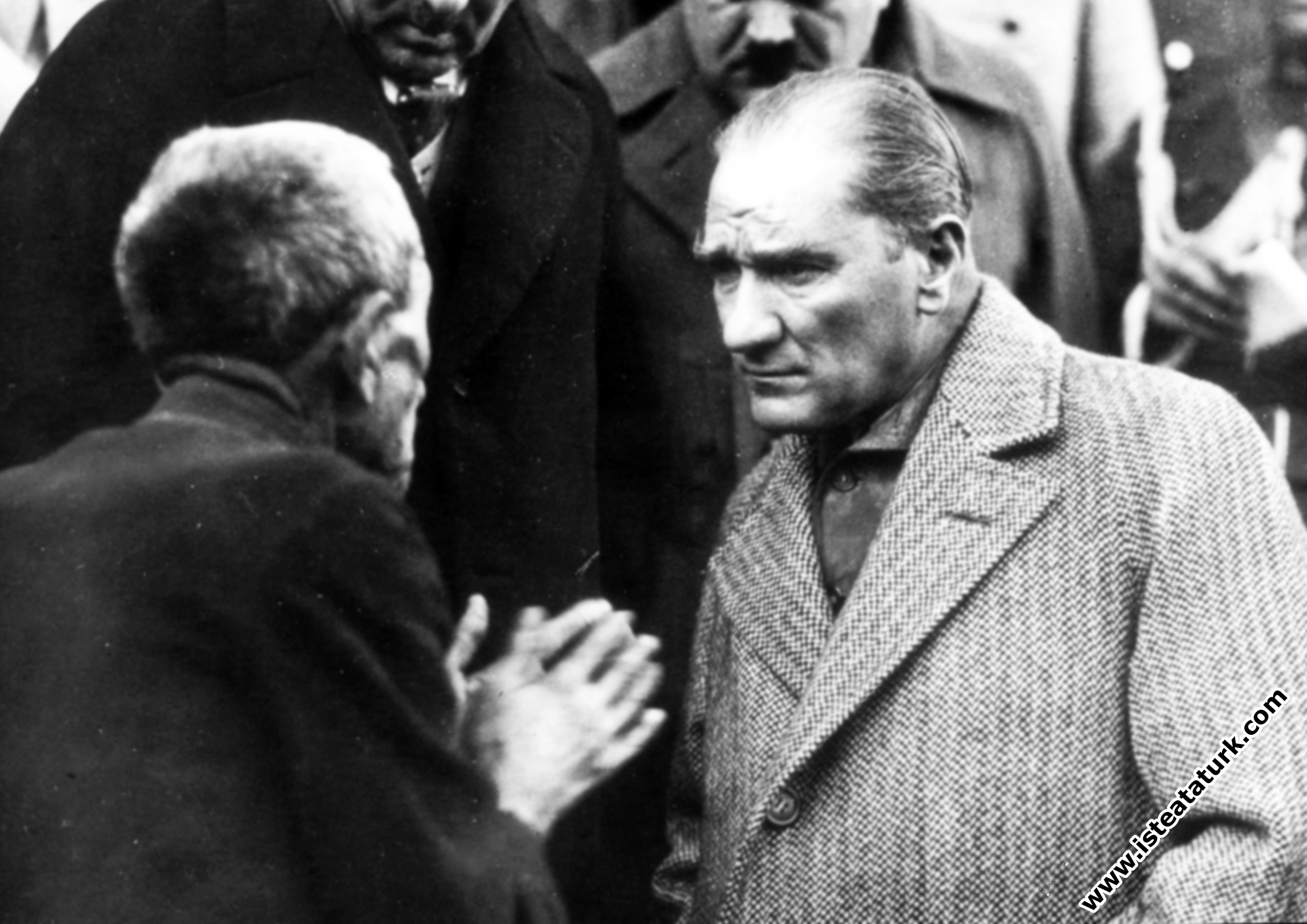

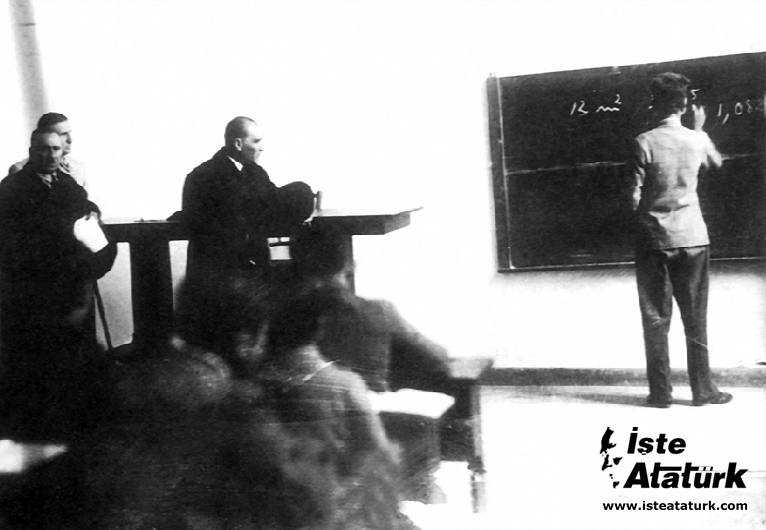

Finally, Atatürk's understanding of populism was not a theoretical view. Populism was a principle that had to be applied in every part of social life and in the most concrete way. That's why we have to take this feature into consideration when examining the working life in this period. Just as Atatürk saw the social groups in the society as equal and unprivileged communities, he also evaluated the workers within the framework of the same populism principle, and the rulers of the period acted in this direction.

As it is known, the Ottoman society was an agricultural society that could not even reach the first stages of industrialization. During the First World War, there were only 76 enterprises that could be called industrial establishments.14 An important part of these were very small hand looms, which we can only describe as workshops today. Naturally, the number of people who could fall into the category of workers in this case was also very limited. According to a census made in 1913, the number of workers was around 17,000, but even this number had fallen to 13,000 in io.i5, probably due to the war. were apprentices.

The real industrialization process of Turkey took place in the Republican period. As it is known, the period of 1923-1929 was a period of recovery, the removal of the wreckage of the Ottoman Empire, and the establishment of a large factory network in the country was not possible in this period. According to the industry census carried out in 1927, the number of workers in the enterprises covered by the Industrial Incentive Law is about 27,000.16 In addition, there are about 25,000 masters and apprentices working in the remaining sector. only 8.94% of the entire workforce consists of organizations employing more than five workers.18 In addition, 22,684 people in this total workforce were children under the age of fourteen. These numerical data show that even in the 1920s, It was not possible to talk about an important working class in Turkey. So the problems of this small group were also minor. The only strike movement we could see during this period was when the tram workers in Istanbul stopped paying wages in 1928, when the British company, in response to the government's policy of nationalizing foreign companies.18

The first social security law of our republic was enacted in this period. However, before moving on to this regulation, it is necessary to mention another law enacted by the Ankara Government even before the Republic, in order to show the tendency of the leading staff on working life. According to this Law enacted on September 10, 1921, the working day in Zonguldak Mining Enterprises was determined to be 8 hours and the minimum wage was determined as 60 kuruş per hour. . The Law dated January 21, 1925, which was the first regulation of the Republican period in the field of work, introduced a one-day holiday requirement for all workers except the agricultural sector. 20 Also, during this period, Work on a comprehensive labor law was going on within the Republican People's Party, and measures were already being taken to deal with problems that could arise from work accidents, strikes, labor disputes and poor working conditions. The draft prepared in 1924 envisaged an 8-hour working day in all branches of industry and aimed to improve health conditions in the workplaces. However, this draft has not passed the National Assembly as a law, as it is not yet comprehensive and detailed enough to be a labor law. Nevertheless, considering that the workers were employed up to 17 hours a day in some workplaces under the conditions of that day, we can say that the above-mentioned preliminary study addressed the most fundamental problem in this field. Precautions were already being taken for problems that might arise from labor disputes and poor working conditions. The draft prepared in 1924 envisaged an 8-hour working day in all branches of industry and aimed to improve health conditions in the workplaces. However, this draft has not passed the National Assembly as a law, as it is not yet comprehensive and detailed enough to be a labor law. Nevertheless, considering that the workers were employed up to 17 hours a day in some workplaces under the conditions of that day, we can say that the above-mentioned preliminary study addressed the most fundamental problem in this field. Precautions were already being taken for problems that might arise from labor disputes and poor working conditions. The draft prepared in 1924 envisaged an 8-hour working day in all branches of industry and aimed to improve health conditions in the workplaces. However, this draft has not passed the National Assembly as a law, as it is not yet comprehensive and detailed enough to be a labor law. Nevertheless, considering that the workers were employed up to 17 hours a day in some workplaces under the conditions of that day, we can say that the above-mentioned preliminary study addressed the most fundamental problem in this field. Since it is not yet comprehensive and detailed enough to be a labor law, it has not passed the National Assembly as a law. Nevertheless, considering that the workers were employed up to 17 hours a day in some workplaces under the conditions of that day, we can say that the above-mentioned preliminary study addressed the most fundamental problem in this field. Since it is not yet comprehensive and detailed enough to be a labor law, it has not passed the National Assembly as a law. Nevertheless, considering that the workers were employed up to 17 hours a day in some workplaces under the conditions of that day, we can say that the above-mentioned preliminary study addressed the most fundamental problem in this field.

The emergence of a real working class in Turkey took place in the 1930s, in parallel with industrialization and structural change in agriculture. The peculiarity of these years is that the obstacles left over from the Ottoman period were removed one by one and a planned industrialization initiative was initiated within the framework of a national economic philosophy. Acting on the principle of rational distribution of scarce resources, all State power was mobilized for the establishment of basic industries, albeit at the expense of neglecting the agricultural sector. At this point, it is necessary to examine two basic developments in terms of the numerical increase of the workforce. The first of these is the establishment of basic industries such as iron-steel, textile and sugar, and the construction of a large railway network throughout the country through state institutions. The importance of this for our subject, naturally, such a breakthrough would create a huge demand for labor. Since a large part of the country's population lives in rural areas and historically there was no settled worker in the cities, the industrialization movement of the 1930s and the factory production that emerged in parallel with this were an important factor in the shift of the rural workforce to the industrial zones. Although, as we will discuss later, the demand for labor created by industrialization could not yet completely and definitively cut the producers from the land, but it was still an important factor in the emergence of a growing labor market, albeit unstable. The industrialization movement of the 1930s and the factory production that emerged in parallel with it were an important factor in the shift of the rural workforce to the industrial zones. Although, as we will discuss later, the demand for labor created by industrialization could not yet completely and definitively cut the producers from the land, but it was still an important factor in the emergence of a growing labor market, albeit unstable. The industrialization movement of the 1930s and the factory production that emerged in parallel with it were an important factor in the shift of the rural workforce to the industrial zones. Although, as we will discuss later, the demand for labor created by industrialization could not yet completely and definitively cut the producers from the land, but it was still an important factor in the emergence of a growing labor market, albeit unstable.

The second development, on the other hand, begins in this period, at a visible rate in the agricultural sector. Again, this should be linked to the industrialization policy of the State. Although the agricultural sector was not generally supported because state institutions created a continuous demand for products such as beet, cotton and tobacco, the producers of these goods were able to make great profits in this period. The producers began to increase the scale of their production, preferring modern technology, modern management methods and the use of wage labor. This, in turn, led to the impoverishment of another segment, for which the State did not create demand for their products, lacking modern production techniques, and generally falling into the hands of moneylenders, and thus seeking new job opportunities.

When looked at within the framework of these two developments, it will be seen that the formation of the labor force or the birth of the worker in Turkey is fed by three basic sources. The first of these are apprentices and even some masters working in traditional handicrafts. In history, the first blow to the establishment of large industrial enterprises was almost always handicrafts and small workshop production. Because this segment does not have the technology, sufficient financial resources and production scale to compete with modern factory production. However, the collapse of these small establishments took longer in countries such as England and France due to the transition to light and intermediate industries before modern factory production. Turkey, on the other hand, wanted to compress its industrialization into a very short period of time under the leadership of the State, and therefore did not experience such an interim period in the industrialization process. This too, In a very short period of time, traditional handicrafts came face to face with modern factory production and collapsed under heavy competition conditions. The fact that the number of masters and apprentices, which numbered 250,000 in 1927, decreased to 180,000 in 1938, shows that many small establishments withdrew from production and their workers became unemployed. 22 We can say that another reason for this decline is that, in the face of competition, the handicraft sector has shifted to more severe working conditions and this has forced many workers to leave the job. This situation was clearly observed especially in traditional carpet and weaving. As a result, some, if not all, of the exposed workers of the collapsing traditional manufacturing sector are employed in modern factory production. It has faced modern factory production and collapsed under the conditions of heavy competition. The fact that the number of masters and apprentices, which numbered 250,000 in 1927, decreased to 180,000 in 1938, shows that many small establishments withdrew from production and their workers became unemployed. 22 We can say that another reason for this decline is that, in the face of competition, the handicraft sector has shifted to more severe working conditions and this has forced many workers to leave the job. This situation was clearly observed especially in traditional carpet and weaving. As a result, some, if not all, of the exposed workers of the collapsing traditional manufacturing sector are employed in modern factory production. It has faced modern factory production and collapsed under the conditions of heavy competition. The fact that the number of masters and apprentices, which numbered 250,000 in 1927, decreased to 180,000 in 1938, shows that many small establishments withdrew from production and their workers became unemployed. 22 We can say that another reason for this decline is that, in the face of competition, the handicraft sector has shifted to more severe working conditions and this has forced many workers to leave the job. This situation was clearly observed especially in traditional carpet and weaving. As a result, some, if not all, of the exposed workers of the collapsing traditional manufacturing sector are employed in modern factory production. The decrease of 000 masters and apprentices to 180.000 in 1938 shows that many small establishments withdrew from production and their workers became unemployed. 22 We can say that another reason for this decline is that, in the face of competition, the handicraft sector has shifted to more severe working conditions and this has forced many workers to leave the job. This situation was clearly observed especially in traditional carpet and weaving. As a result, some, if not all, of the exposed workers of the collapsing traditional manufacturing sector are employed in modern factory production. The decrease of 000 masters and apprentices to 180.000 in 1938 shows that many small establishments withdrew from production and their workers became unemployed. 22 We can say that another reason for this decline is that, in the face of competition, the handicraft sector has shifted to more severe working conditions and this has forced many workers to leave the job. This situation was clearly observed especially in traditional carpet and weaving. As a result, some, if not all, of the exposed workers of the collapsing traditional manufacturing sector are employed in modern factory production. We can say that the handicraft sector has moved to more severe working conditions and this has forced many employees to leave the job. This situation was clearly observed especially in traditional carpet and weaving. As a result, some, if not all, of the exposed workers of the collapsing traditional manufacturing sector are employed in modern factory production. We can say that the handicraft sector has moved to more severe working conditions and this has forced many employees to leave the job. This situation was clearly observed especially in traditional carpet and weaving. As a result, some, if not all, of the exposed workers of the collapsing traditional manufacturing sector are employed in modern factory production.

The second source that feeds the industrial workforce in Turkey has been the impoverished small peasants. The impoverishment of this group, the loss of its land and finally starting to look for a job did not happen in a short period of time, nor did it develop due to a single reason. The separation of the peasant from the land has always been one of the most difficult developments in history. However, we can say with certainty that this process started in the period we are examining and gained momentum in the 1950s and 1960s. As we have said before, the most important role in this was played by the government's policy of purchasing agricultural products. State institutions create a constant demand for certain agricultural products and industrial raw materials, On the one hand, it has had a stimulating effect on the manufacturers of these products by guaranteeing their long-term profits, on the other hand, it has left a victim to another segment that produces other products completely depending on climatic conditions and faces marketing difficulties at any moment. According to the plan, since industry was given weight in the agriculture-industry dilemma, it became very difficult for these small peasant producers to obtain sufficient and timely credit, fertilizer and agricultural tools. As a result, some of these producer families began to look for other means of subsistence by selling their lands and became agricultural workers, often working for wages on the same land or in the surrounding villages. 23 Others left their families in the village and either entered seasonal jobs or sought employment in industrial centers. Here is this transformation in agriculture, Ultimately, it formed the core of the industrial workforce, even if it did not lead to a complete break with the land at first. It should be added, however, that usury played a major role in the fact that some peasants became poorer and eventually landless.24 Many peasant families, who could not sell their crops or get loans, fell into the hands of moneylenders and had to sell their lands, unable to pay the very high interest rates.

The third source that feeds the wage labor supply in Turkey is the peasantry, which we call sharecroppers and farmers, who rents someone else's land by dividing the product. The value of the land in the regions where it is produced has increased gradually as a result of this practice. In this case, instead of having someone else work their land and sharing the product with him, the landlords themselves produced and marketed it. This has led many peasant families, who do not have their own land and whose entire livelihood consists of sharecropping or farming, to seek other means of livelihood. Although there is not much reliable source on this subject, a study conducted in 1963, In the period we examined, the ratio of sharecropper and splitter families in total rural families decreased to 2.6-3.3%.26 Although we do not have numerical data on previous periods, many regional studies show that sharecropper and splitter families have a much larger proportion in the traditional society. showed. 27

Although the industrial workforce in Turkey is mostly fed from these three basic sources, there was no complete separation from the land in this period. The most important reason for this is that landless peasants and unemployed masters and apprentices work in rural areas where the industry-agriculture distinction is not yet clear. As a result of the quotas and prohibitions placed on the import of agricultural machinery and tools in the growing farms, labor and intensive technology gained importance, and thus, while the small peasant producers were left without land, they were again employed in these farms for wages. In addition, in our society, where mass media and social mobility (mobility) have not yet developed, the attractive effect of cities and industrial zones has remained at a minimum level. However, despite all these obstacles, the number of workers in the industry was 27,000 in 1927; this number increased to 55,321 in 1932, to 77,400 in 1935 and finally to 100,596 in 1938.28 These numbers do not include those working in state industrial establishments. Considering these, we can talk about the presence of 3,500 workers in sugar factories, 7,500 workers in Sümerbank factories, 1,500 workers in İŞ Bankası affiliates and 20,000 workers in mining facilities affiliated with Etibank. In this period, there was not a fully settled and concentrated working class in industrial areas. To give an example, according to Webster, 3,000 people had to work a year in order to employ 2,000 workers continuously at the Kayseri Cloth Factory. Zonguldak Coal Mines was another typical example of this. Every year, an average of 25,607 people from the surrounding villages had to come to the mines so that only then, an average of 15,808 workers could be employed. 30 Naturally, we can also attribute this situation to not being completely disconnected from the soil.

Labor Legislation and the 1936 Labor Law

Although there was no demand from the grassroots, the labor legislation, with some shortcomings and which cannot be considered very modern today, but could undoubtedly have long-term effects compared to that period, was enacted with great determination by the Republican administration. We can only evaluate this phenomenon within the framework of the populism principle that we have examined before.

Instead of leaving the strong and the weak alone, or leaving a group that has not yet reached the level to defend its rights, to its own fate as a State, intervening for the benefit of the weak and unorganized made great sense in the conditions of that period. Now, in the light of this evaluation, we can look at the developments in labor legislation. The Health Law of 1930, which preceded the 1936 Labor Law, was a preparatory or preliminary study in this field. Although this Law brings a very limited regulation, it has also been able to deal with issues that had not been considered until that time. According to the law, maternity leave is determined as six weeks and the employment of children under the age of twelve in the industrial sector is prohibited.31 According to another provision of the law, it is prohibited to employ children under the age of sixteen on night shifts. In addition, the maximum daily employment in underground and night works is limited to eight hours. Finally, according to the same Law, establishments employing more than fifty workers are required to have a doctor for every fifty workers.

After that, the 1936 Labor Law No. 3008, which was the most important and most comprehensive law of not only that period, but also a large period extending up to the 1960s, came into force. As it is known, the first draft of this Law, whose first draft could not be passed by the Parliament in 1924, was finally accepted twelve years later. This Law, which prioritizes social solidarity in the introduction and adopts the resolution of disputes through the State, was not only considered as a labor legislation, but was put into effect as an element of social balance. 32 The provisions of the law would apply to establishments employing at least ten workers. Article 35 limited the maximum weekly work to 48 hours, including establishments operated on Saturdays. 33 It would not be possible to work more than nine hours in a day. As for overtime, according to article 37, It could not be done without the consent of the worker and could not exceed three hours a day. 34 Overtime days, on the other hand, could not exceed 90 days per year. Pursuant to Article 50, women and children under the age of eighteen were prohibited from working in any underground, underwater or night work. 35 Health conditions are regulated by Articles 55 and 63; The Ministry of Labor and Health was authorized in this regard. 36 According to this Law, where strikes and lockouts were prohibited, labor disputes would be resolved through employer and worker representatives (Article 77). Disputes that could not be resolved in the meetings of employer and worker representatives would necessarily be brought to the Supreme Arbitration Board. Occupational accident, occupational disease, old age, Compensation provisions arising from disability and unemployment and assistance to the worker's family would be regulated by the State and a Workers Insurance Institution would be established for this purpose in the future (Article 100). 38

Naturally, there were some points left open by this Law. For example, paragraph 6 of Article 35 authorized the government to extend the working day when necessary. This authority would indeed be used frequently in the following war years, and a normal working day, which was thought to be eight hours, would almost disappear permanently.39 Moreover, instead of judicial review in labor disputes, the mandatory arbitration of the State, in a country where a significant portion of the workers were employed in state institutions. would show the state as a party in this area. However, despite all this, In our country, where no regulation was made in any corner or stage of the working life before, the 1936 Labor Law should be considered as a giant leap, a great leap forward. All these developments show how advanced the Atatürk period was in the history of the Republic. It is a question of looking at a society and its sections. The principle of populism, which gave this view, was able to reconcile the realities of the West and Turkish society, which left these stages behind, on the one hand, and on the other hand, it was able to transfer abstract ideas to concrete social life.

In history, we have to evaluate each period in its own structure, conditions and variables. In this respect, Turkish economic and political history is beyond our subject; With this article, we are once again emphasizing the developments and importance of the Atatürk period in our working life.

1 G. Runkle, A History of Western Political Theory, New York 1968, p. 180-201.

2 EJ Hobsbawm, The Age of Revolution, New York 1962, p. 278-284.

3 W. Godwin, Inquiry Concerning Political Justice, London 1798, p. 136.

4 G. Sabine, A History of Political Theory, New York 1961, p. 517-542 and 575-597.

5 G. Runkle, A History of Western Political Theory, New York 1968, p. 256.

6 A. Quinton, Utilitarian Ethics, New York 1973, p. 1-11; E. Halevy, The Growth of Philosophic Radicalism, London 1928, p. 1-35.

7 W. Godwin, Inquiry Concerning Political Justice, London 1798, p. 149; E. Halevy, The Growth of Philosophic Radicalism, London 1928, p. 193-202.

8 R. Keat, J. Urry, Social Theory as Science, London 1975, p. 9-35.

9 Z. Toprak, “The Formation of the Ideology of Populism”, Economic and Social Problems of Atatürk Era, Istanbul 1977, p. 14.

10 ibid, p. 18-19.

11 ibid, p. 26.

12 T. Timur, Turkish Revolution and After, Ankara 1971, p. 131-14.

13 Z. Toprak, “The Formation of the Ideology of Populism”, Economic and Social Problems of the Atatürk Era, Istanbul 1977, p. 20-21.

14 BC Yazman, Turkey's Economic Development, Ankara 1974, p. 40.

15 ZY Hershlag, Turkey, The Challenge of Growth, Leiden 1968, p. 61.

16 Statistical Yearbook 1930, p. 187.

17 SM Rosen, “Turkey”, Labor in Developing Cuontries, ed.: W. Galenson, Berkeley 1962, p. 252.

18 Statistical Yearbook 1930, p. 196.

18 A. Işıklı, Unionism and Politics, Ankara 1972, p. 295.

19 M. Alpdundar, “Ereğli Coal Workers and Union Activities”, Social Policy Conferences, Istanbul 1965, p. 133.

20 C. Sawdust, Social Policy, Ankara 1967, p. 189.

21 K. Boratav, Distribution of Income in 100 Questions, Istanbul 1972, p. 121.

22 Statistical Yearbook 1942-1945, p. 296.

23 KH Karpat, Turkey's Politics, Princeton 1959, p. 109.

24 K. Boratav, Distribution of Income in 100 Questions, Istanbul 1972, p. 123-127.

25 H. Ülman, F. Tachau, “The Attempt to Reconcile Rapid Modernization With Democracy”, The Middle East Journal, Spring 1965; KH Karpat, supra; K. Boratav, ibid.

26 K. Boratav, Income Distribution in 100 Questions, Istanbul 1972, p. 129.

27 O. Tuna, “A Study in the East and Northeast Regions in terms of Labor Flow to Western Countries”, Social Policy Conferences, Istanbul 1966; A. Araş, Land Ownership and Operation Types in Southeastern Anatolia, Ankara 1953.

28 Statistical Yearbook 1942-1945, p. 296.

29 DE Webster, The Turkey of Atatürk, Philadelphia 1939, p. 257.

30 M. Alpdundar, “Ereğli Coal Workers and Union Activities”, Social Policy Conferences, Istanbul 1965, p. 138.

31 C. Sawdust, Social Policy, Ankara 1967, p. 191-192.

32 ZY Hershlag, Turkey, The Challenge of Growth, Leiden 1968, p. 291.

33 N. Eren, Turkey, Today and Tomorrow, New York 1963, p. 149.

34 ibid, p. 150.

35 ZY Hershlag, Turkey, The Challenge of Growth, Lieden, 1968, p. 291.

36 N. Eren, Turkey, Today and Tomorrow, New York 1963, p. 150.

37 ibid, p. 150.

38 ibid, p. 150.

39 Labor Problems in Turkey, ILO, Geneva 1950, p. 37.

40 FH Treasurer, Systematic Turkish Labor Law Legislation, Istanbul 1953, p. 282-306.

Muharrem Tünay

Source: ATATÜRK ARAŞTIRMA MERKEZİ DERGİSİ, Sayı 5, Cilt: II, Mart 1986